The name Arthur Balfour means little to some and everything to others. To those of us who traipsed past his statue on our way to the launch of the Balfour Apology Campaign one Tuesday evening in October, he was as similarly unrecognisable as the various faces that adorn the walls of the Houses of Parliament. Hosted by the Palestinian Return Centre and Baroness Jenny Tonge, journalists, activists and those who stand in solidarity with the Palestinian people packed into a room in the House of Lords to consider the lasting impact of 67 words written by a man who himself is consigned to the annuls of history, while his legacy lives on.

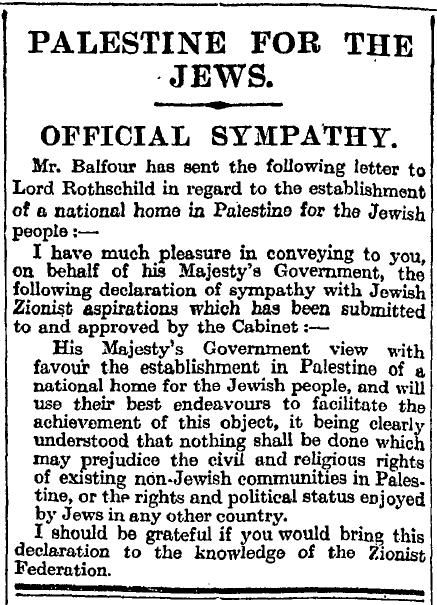

In a letter to the British Jewish community leader Walter Rothschild in November 1917, Arthur Balfour (then the British Foreign Secretary) committed the British government and its subsequent mandate over Palestine to facilitating the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. While intentionally vague in its use of terminology, opting for “homeland” over “state”, the document would nonetheless go on to influence and define British policy in Mandatory Palestine and allow high levels of Jewish immigration and land purchasing. The particulars of what Britain envisioned for this small piece of land on the Eastern Mediterranean remains unclear, but what we do know is that it set the people who inhabit its hills and plains, coastlines and cities, on a collision course they are yet to emerge from.

As the members of the panel, Majed Al-Zeer (President of the Palestinian Return Centre), Karl Sabbagh (Historian and Writer) and Betty Hunter (Honorary President of the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign) made eloquently clear, the Apology Campaign would be asking the current British government to acknowledge, and take responsibility, for its part played in the creation of a conflict which is now approaching its 70th year (if we begin in 1948, that is). The campaign goes beyond the document itself, while acknowledging what an uncomfortable relic of British colonial rule it is, to consider why the British government felt they could promise political rights to one group at the expense of another. It didn’t take British officials on the ground long to see the Declaration as an insidious error of judgement, with the High Commissioner for Palestine referring to it as a “colossal blunder” only a decade after it was written. Today, ninety years later, this same sentiment has found its way back to the British establishment.

The aim of the Apology Campaign is to use the centenary of the Declaration in November 2017 as a moment to put Palestine and Palestinians back on the agenda, and for the British government and public alike to discuss its own historical role in this sorry saga. Nevertheless, how the evening came to be reported in the British media in the following days raised even more important questions as to how far we’ve really moved on from our colonial past.

The launch event was open to the public, live streamed on Facebook and recorded live by an Israeli Radio station at the request of the campaign organisers. The panel was followed by a time for questions from the floor, which would come to cause the controversy of the night. The last question was made by an Orthodox Jewish gentleman expressing his own distance from the State of Israel, before continuing to make almost inaudible, muffled comments about a relationship between Jewish-American economic policy and the Nazi resort to the Final Solution. Baroness Tonge, chairing the evening, quickly moved on, herself clearly unsure of the details of the gentleman’s comments, but not wanting to engage him any further.

Within two days Baroness Tonge would be suspended and then resign from her party, the Liberal Democrats, with the event being lambasted as shameful by the Israeli Embassy in London and another UK minister being “genuinely horrified”. The launch event would be exclusively reported on in light of the suspension/resignation, and the comments made by the one Orthodox gentleman. How did an evening of open discussion and conversation about an issue as critical as the ongoing Israel-Palestine conflict become hijacked in this way? In the newspaper articles that followed the wider issues where given limited coverage, while the controversial comments given particular emphasis. The reports in the media over the next few days included grave errors, referring to this gentleman as one of the speakers and claiming that the audience erupted into spontaneous applause after his comments. As an attendee of this event, I can categorically say that this was not only irresponsible reporting, but also dangerous false accusations of anti-Semitism.

Anti-Semitism matters and is deplorable, for all it has caused in the past and the damage it still does today, and those engaged in the public arena should be careful to never incite ethnic/religious stereotypes or hatred in order to gain support. However, what was discussed that evening at the Apology Campaign launch; the role of the British government in the traumatic rupture of a place and its people, an ongoing refugee crisis, the prolonged lack of political rights for Palestinians, and not to mention the continual use of violence by both Israelis and Palestinians, should not be considered anti-Semitic. While Britain claims to be a nation which prides itself on tolerance and freedom of speech, this event and its subsequent fallout have made abundantly clear that we do not have the empathetic imagination nor the depth of language to talk constructively about these issues. Or maybe we just don’t want to?

Yet can we afford not to? This topic isn’t something that can be swept under the rug. There are people willing and ready to have these difficult conversations, to use their right to freedom of speech to dredge our own colonial misdemeanours up from the archives and consider the effects they still have on the rights of others today. All the issues discussed that evening and subsequently matter; displacement, dispossession, occupation and anti-Semitism, but we should not be drawn in by spurious reporting and exclusive understandings. Rather, we should see them as manifestations of the same issue; an inability to see and respect human worth in all its forms.

I came away from my time in those hallowed halls uneasy. As we filed out of the Palace of Westminster, the faces of those historical leaders who carved up the world with little consideration for those it would effect, watched down upon us. Smug or in eternal blissful ignorance, I couldn’t decide. It would be 48 hours before my phone flashed with the news articles discussed above, yet I couldn’t help notice the irony of where we had spent the last two hours. The term post-colonial entered our lexicon decades ago, but how this event would be documented in our own British press made me doubt whether we are able to even talk in such a way. In many ways the Balfour Declaration should not be considered rare or exceptional, but as one artefact of many from a bygone era where men in Westminster called the shots over people’s destiny in far-away lands. The difference is that in this case, this particular artefact is still alive and well, causing continual strife and suffering.

Image: The Declaration as it was printed in The Times on November 9, 1917 (Wikimedia)